- Home

- Christian Giudice

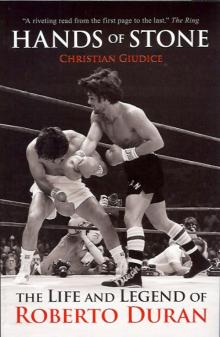

Hands of Stone

Hands of Stone Read online

HANDS OF STONE

The Life and Legend of Roberto Duran

Christian Giudice

MILO BOOKS LTD

Worldwide Praise for HANDS OF STONE

“In the age of the tabloid we know more about many of our sporting heroes than we ever cared to know, but from the time he blasted his way into our consciousness with a punch to the scrotum almost four decades ago, Roberto Duran had been an elusive and enigmatic figure. With Hands of Stone, Christian Giudice has separated the wheat from the chaff in the most illuminating deconstruction of a mythic ring legend since John Lardner went toe-to-toe with the ghost of Stanley Ketchel.”

George Kimball, author of Four Kings

“My favourite book.”

Ricky Hatton, former three-time world champion

“Christian Giudice has succeeded brilliantly in separating the myth from the legend and produced a book that serves only to enhance further the reputation of an already astonishing fighter...Hands of Stone is the dazzling account of a breathtaking fighter and a remarkable man.”

The Independent

“A cracking book.”

Daily Star

“The first – and definitive – account of Duran’s extraordinary life both in and out of the ring.”

Boxing Digest

“Duran’s 120-bout career is vividly chronicled.”

The Independent On Sunday

“Compelling.”

The Sun

“A must for all fight fans.”

Liverpool Echo

“A gripping biography. Every page will keep readers enthralled.”

Dublin Evening Herald

“A profoundly detailed reconstruction of Duran’s world.”

Gerald Early, Belles Lettres, A Literary Review

“What a story!”

Scotland on Sunday

“If you buy only one boxing book this year, Hands of Stone should be it.”

Boxing Monthly

This electronic edition published in 2011

Copyright © Christian Giudice

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

MILO BOOKS LTD

www.milobooks.com

[email protected]

I am not God but something very similar.

Roberto Duran

To my mother – who faced down a deadly disease – and beat it.

To my father, a fighter, a man, my hero – who once threw a perfect left hook on Schellenger Ave. (between Atlantic and Pacific Aves.) on a summer night in Wildwood. Thank you for protecting us all of these years. I wrote this book for you, Pop.

Contents

Prologue

1 Hunger

2 Fighter

3 Papa Eleta

4 Streetfighting Man

5 Two Old Men

6 The Scot

7 The Left Hook

8 Revenge

9 Hands of Stone

10 “Like A Man With No Heart”

11 Esteban and the Witch Doctors

12 “The Monster’s Loose”

13 El Macho

14 “No Peleo”

15 King of the Bars

16 Return of the King

17 Redemption

18 Tommy Gun

19 “I’m Duran”

20 The Never-Ending Comeback

21 The Last Song

Notes

Acknowledgments

Roberto Duran’s Fight Record

Prologue

“We mustn’t be afraid of violence. Hatred is an element of struggle; relentless hatred of the enemy that impels us over and beyond the natural limitations of man and transforms us into effective, violent, selective and cold-blooded machines.”

Che Guevara

IT IS 26 NOVEMBER 1980 and Roberto Duran Samaniego stands naked in the middle of the ring. His arms sulk by his sides. He feels weak. His body has betrayed him, as he has betrayed himself. His eyes, the twin beacons of his demonic aura, search for the exit.

Always defiant, tonight he bleeds compromise. It is like watching a Ferrari sputtering to the closest gas station. With sixteen seconds remaining in the eighth round in the Louisiana Superdome, his mocking, face-pulling, showboating challenger, Sugar Ray Leonard, has affronted his dignity and stripped him of his macho. And so he breaks the contract that he signed the day he stepped in the boxing ring: To punch till the end. Duran has always boxed like he cursed, in quick, immediate thrusts; now the roughest, toughest, most feared fighter in the world raises his left hand and walks away.

“No quiero pelear con el payaso,” says Duran. I do not want to fight with this clown. He repeats the words, but a ringside broadcaster claims to hear him say “no más,” the Spanish for “no more.” The phrase will live in sporting infamy.

After a second, Leonard’s brother Roger yells, “He quit on you Ray.” Leonard runs over and jumps on the ringpost. The fight is done.

People would later dub the man a coward, a fake, a phony. They said laziness and gluttony had precipitated his downfall; fame had accelerated it.

The first part of Duran’s career, his life, was over. Act Two was about to begin.

EVEN BEFORE I went to Panama, I knew one thing for sure about Roberto Duran: The man was not a quitter. I didn’t understand the contradictions of the no más fight but also didn’t buy into the hype. When I told people that I was headed to his homeland, they joked about the infamous moment when he left the ring seven rounds early. “Tell him ‘no más’ for me,” they said.

With a face that reminded some of Che Guevara, others of Charles Manson, Duran’s feral stare never left me. His look was compelling, his image enigmatic, his fighting skills unsurpassed. In the ring, Duran came forward and intimidated; he didn’t know any other way. Those who stood up to him paid the price in blood and hurt; those who ran were pursued and hunted down. Sportswriters devoured stories of his wild childhood, told of him swimming across bays with a bag of mangoes held in his mouth to feed his family. His eyes were “dark coals of fire” and anything that he sneered at “froze” in terror. But who was this man? Was he really pure evil lodged in the body of a 135-pound prince, or was it all an act?

Even when his ability to intimidate had waned, the Doo-ran, Doo-ran cheers still echoed around sold-out arenas. Even when he was only a quarter of his former self, a sad, overweight Elvis making his last call, he was still Duran. Watching those final years of futility it became clear that legends never die, they just age. So when the thought of finding and telling the Duran story crept into my head, I couldn’t resist. With the purpose of finding this man, I decided to leave my job, friends and family and head to Panama City. I had a smattering of Spanish, a laptop and some old Duran fights on tape. I didn’t even know if he spoke English, or how well.

I was six years old on that November night in New Orleans in 1980. I wanted to know about the young Duran, the kid whose face came to be plastered all over Panama City, and how someone who had nothing became a symbol for hope in a Third World country that suffered every day. I wanted to see how the mere glimpse of Duran’s smile could make a difference. Few people have the influence on a country as Duran does in Panama and the only way I would understand it was to follow him there. The only way I could comprehend the strength, the character of this man was to eat patacones and empanadas with his people, sip coconut juice straight from the fruit, dance salsa, and listen to the music of Osvaldo Ayala, Los Rabanes or Sandra y Sammy. I had to go to

Guarare and the gyms in Chorrillo to let the legend seep into my blood amid the 100-degree heat. All his old managers, promoters, friends and schoolteachers would have something to say and I had to absorb it.

Finding him was another story. Somehow in Panama everyone knows Duran personally. He is everyone’s buen amigo. So when a taxi dropped me off at Duran’s home in the El Cangrejo neighborhood the night I arrived, I knew I was onto him. Duran never showed that night, but I knew deep down that I would find him and learn the secrets that many in Panama claimed already to know. “That’s the reason that many people respect him because he never forget where he come from,” said Chavo, his oldest son. “He’s humble and always told me, ‘Remember I’m from El Chorrillo, a poor neighborhood, so you have to be humble.’ The people respect that. He’s always helping the poor people, especially with the kids. People like that.” In a country of less than three million souls where many live on less than a dollar a day, that counts.

The boxing scene in Panama is a story in itself, a gallery of memorable, glittering characters. Every gym tells a tale. One couldn’t go into the Papi Mendez Gym without seeing Celso Chavez Sr. in a corner cajoling a fighter while his son Celso Jr. wrapped the hands of another prospect. Look closely and there was the prince of Panamanian boxing, two-time lightweight champ Ismael “El Tigre” Laguna, playing dominoes with friends on a corner, or light-flyweight champ Roberto Vasquez knocking an opponent senseless in an El Maranon Gym. Dozens of boxing lifers greet people at the entrance to Panama’s most popular gym Jesus Master Gomez in Barraza, while Yeyo “El Mafia” Cortez and Franklin Bedoya reminisce at the Pedro Alcazar Gym in Curundu. Young fighters mimic two-time world champ Hilario Zapata’s squatting defensive style or Eusebio Pedroza’s brilliance off the ropes. They listen closely to caustic woman trainer Maria Toto as she barks instructions in a gym in San Miguelito, while others hone their skills in Panama Al Brown Gym in “the cradle of champions,” Colon. All the while, the sounds of “yab, yab, yab” filter through the heat. And no one in Panama would even know about boxing if it weren’t for the voice of the isthmus, Lo Mejor de Boxeo’s Juan Carlos Tapia, a man who spits quick-witted Tapiaisms at a feverish rate. Most of the twenty-three (at the time of writing) living world champs meet for reunions at local cards, while boxing wannabes throw combinations in the corners at amateur bouts. Sit down at fight night, grab a local Atlas beer or a bucket of ice with a bottle of Seco-Herrano, a chorizo meat kabob, and prepare for bedlam. You never know what might happen.

“I am Duran,” the man used to say after fights, as if the statement spoke for itself. Pure and simple, nothing more or less, just the exclamation that there was not another human on this earth like him. In the ring, there wasn’t. With his blend of skill and ferocity, the greased back hair and sharp beard, the man they called Cholo (for his mixed Indian heritage) had the best boxers of his generation against the ropes. Duran in full flow was a curious but riveting combination of in-your-face chaos and relentless beauty. As a person he lived just as freely, without caution.

Roberto Duran knows about pain. He knows what it’s like to make an opponent succumb before stepping foot in the ring. He knows, inside in his corazon, his heart, what it’s like to watch a man feel fear. For he did that with a look, one brazen, cocksure glance that had those same men trembling as they taped their hands or worked up a pre-fight sweat. He did it often, and with aplomb, stole men’s hearts without trying. That was Duran.

Roberto Duran knows about torture. He knows what it’s like to crowd a man, stick him in the ropes, rake his eyes with his beard, jumble his senses with a short hook, bust him below the belt, thumb him, break his will with a running right hand. He knows what it’s like to make a man cringe with every punch, break him down so thoroughly so that he would never return the same again. Some never recovered, and they saw that face, that beard, those eyes, and were reminded of the man every time they threw a punch, feinted, jabbed. It was Duran, that face, that look.

Roberto Duran knows about struggle. He knows what it’s like to spend his childhood finding ways to provide for his mother. He knows about living with nothing – and still reaching in his pocket to give to others. He knows about poverty, disease, sorrow – and how to dissolve tears with a smile. That’s Roberto Duran.

Roberto Duran knows about ecstasy. He knows the feeling of beating a man, an idea, a creation, a nation, to believe there wasn’t another human on earth who could challenge him. He knows what it’s like to hang through the ropes with tears rushing down, and hear an entire arena sing an anthem in his honor. He knows what it’s like to have an entire country on his back and feel their weight each time he throws a punch. He knows what it’s like to deleteriously fall, rise again, and return home to thousands calling his name. He knows what it’s like to face a monster, a fear, and vanquish it. That was Duran.

Roberto Duran has felt pain. And he knows about sorrow. He is a man who has felt every human emotion to excess, and expressed his reactions for the world to see. Not since and maybe never again will there be a boxer quite like him. Duran was an entertainer, a brute, a fighter, a lover, a loyal friend, an artist. In his prime he took the top fighters in the world and stripped them of their pride.

But the one time in New Orleans in 1980, he lost his. Unfortunately for many people, that’s all that counts.

Christian Giudice

1

Hunger

Blessed be the Lord my rock/Who trains my hands for war/And my fingers for battle

Psalm 144:1

DONA CEFERINA GARCIA was looking for her husband – and she had a good idea where to find him. Rumors in the tough barrio of El Chorrillo had him drinking in a bar with another woman. That was bad enough, but their teenage daughter was due to give birth any hour, and Ceferina’s services would be required to deliver the baby. It was hardly the best moment for the new child’s grandfather to disappear with some puta, some whore. Ceferina, eyes blazing, mouth set and fists clenched, was on the warpath.

The bar stood next to a concrete apartment block known as La Casa de Piedra, the House of Stone, on North 27th Street; Apartment A, Room 96, to be precise, was where her daughter Clara lived and was already going into labor. Ceferina entered the bar with fists clenched and there was her husband, Jose “Chavelo” Samaniego, in the corner with a local girl. Ceferina took in the scene with a look of fury. Many women in Panama turned their heads from the Latin games their husbands played but she was not one of them. Both poverty and inclination had made her a fighter; she had once been thrown in jail for punching the local mayor.

With one fast right hand, she left Chavelo lying on the sticky bar floor and headed back to her daughter.

Ceferina would bequeath her power to her grandson, born just hours later when her daughter Clara pushed eight-pound Roberto Duran Samaniego into her hands on June 16, 1951. They rushed the bloody boy to the Santo Tomas Hospital in a taxicab. “He was born in a stone house, and fell right in my mother’s arms at six o’clock in the afternoon,” said Clara years later, squatting to illustrate the trajectory of the baby. She named him Roberto after his uncle, the brother of his father Margarito.

Clara was young, not much more than a girl, but the child was already her fourth. Motherhood started early in Panama. She came not from Chorrillo, a poor area of downtown Panama City, but from Guarare, a small town in the Los Santos province in the interior. It has a central square, a couple of bars, a church, a gas station, a hardware store, a small downtown area with banks and markets, and a field which once held an old bullring. A symbolic guitar greets visitors at the town’s entrance and Guarare is chiefly known for its Feria de la Mejorana, a folk music festival every September that attracts the country’s best dance groups and waves of visitors. The highlight is the simple, classy La Pajarita dance. Women wear pollera, a dress made of linen and lace decorated by flowers, while men in their best suits drink Seco, a pungent liquor produced in the town of Herrera.

Young, curvaceous and willing, the

teenage Clara made men look her way. Though not conventionally beautiful, her allure filtered through her eyes. The young Clara flaunted her flowing brown hair and full figure. Her inviting gaze comforted, made men feel wanted. That was her magic. Instead of prodding, Clara caressed; instead of rushing, she glided. She was tender, soft, gentle and generous with the little she had. People who knew her as a teenage mother remember a sweet girl striving for a better life for her children. “She was very pretty and very elegant,” said her sister Mireya. “Many men were interested in her but she had bad luck. She had many children, but had to cope with much.”

With one exception, all of her men were strong Latin types who took her to bed then hit the road. First, she had a son to a Puerto Rican and named him Domingo, though everyone called him “Toti.” His father did not stick around. “He abandoned me in 1950 because my mother had some problems with him,” said Toti. “He wanted to take me but my mother did not agree to this, so I did not see him again.” After her Puerto Rican lover left, Clara had a brief fling with a Filipino and bore him a daughter, Marina.

Hands of Stone

Hands of Stone